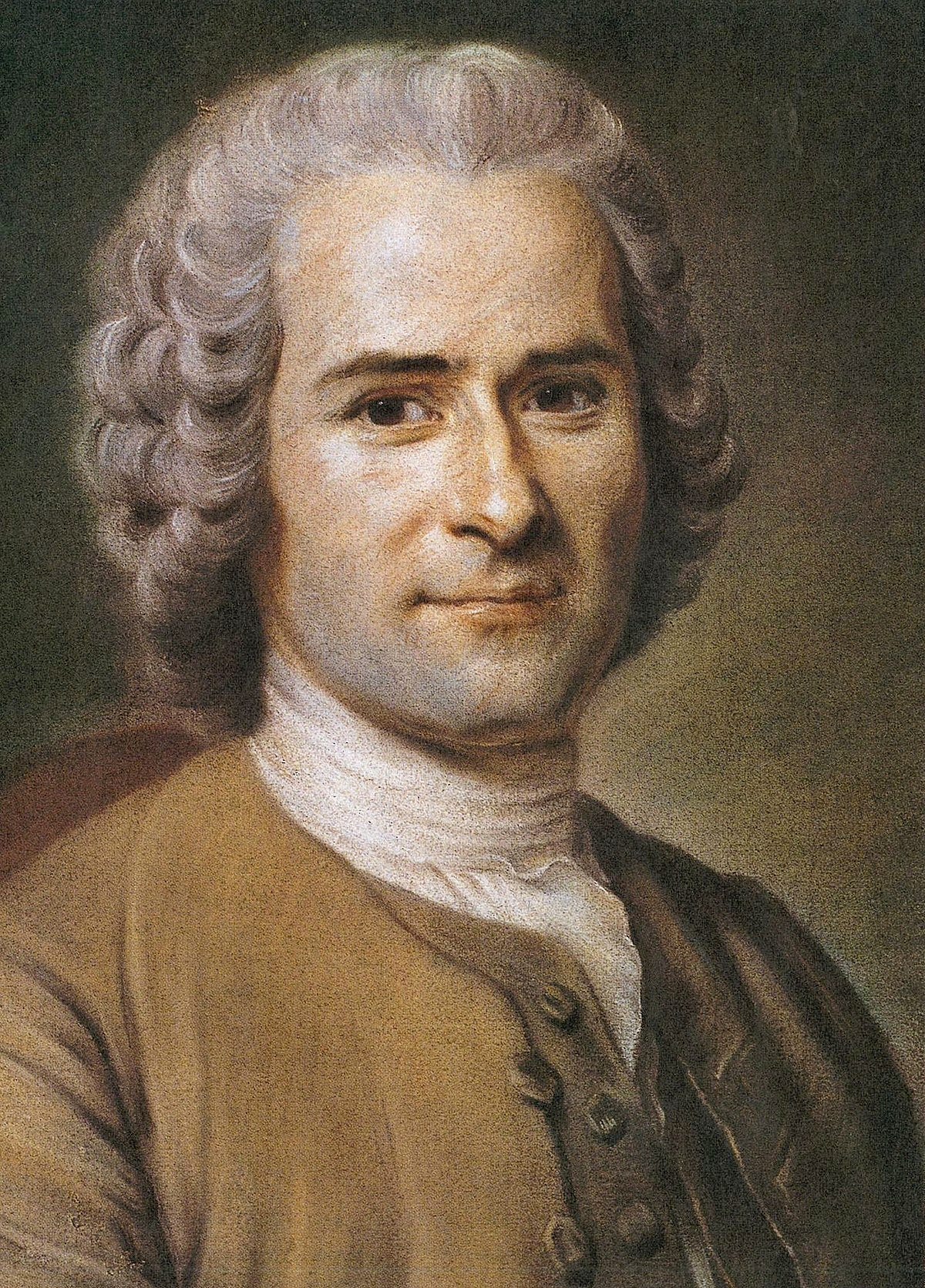

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Musician

Charting the musical life of the 18th Century Philosopher, through the lens of his seminal 'Confessions'

Charting Rousseau’s Musical Journey

In The Confessions, there are five books in which Rousseau dedicates significant literary resources to exploring his relationship with music. These are books three, four, five, seven and eight. Whilst it is valuable to consider Jean-Jacques’ musical development chronologically, I propose that it is also very useful to divide the books thematically. Books three, four and eight belong together, as they paint the musical life in romantic, aspirational terms, and speak to Rousseau’s inner drive to achieve public recognition as a musician. They are also concerned with the formation of a kind of musical telos, and the awakening of Jean-Jacques artistic passions.

In book three, we observe the awakening of Rousseau’s musical spirit. Book four canvases Rousseau’s inadequacies, and the humiliations he must bear on his journey to artistic absolution. This prepares the way for a resurrection of fortunes in book eight, when Jean-Jacques finally achieves the recognition he desires, in the triumphant reception of his opera, The Village Soothsayer.

But the public triumph of Rousseau cannot occur without him first exploring a necessary period of growth and development in musical skill, which sets up the relationship between books five and seven. Rousseau’s writings on music in these two sections are largely concerned with the serious craft of music, and demonstrate his considerable commitment to consolidating his technical skills. In book five this lies is the heavy work of developing a musical technique, exploring Rousseau’s extraordinary capacity for autodidacticism. In book seven, this concerns the authorship of his treatises, and his desire to make deliberate, impactful change on the musical world through his own system of musical notation, his writings, and his engagement with the academy.

This is not to say that each one of these books (and the other chapters which contain more of Rousseau’s reflections on music) adhere strictly to this kind of thematic distinction. Rousseau, of course, does not write that way, and there is an ebb and flow to all these ideas throughout every chapter of The Confessions from book three onwards. However, each book contains distinct and purposeful writing which explores specific aspects of Rousseau’s musical character. This character may be better organized in the reader’s mind by understanding the books in these groupings.

Rousseau’s juvenile temperament: Problem in search of an answer?

Notwithstanding the brief mention of his Aunt Suson’s influence in childhood, Rousseau begins to chart his relationship with music in book three of The Confessions. At the opening of the book, we find Rousseau as a disturbed, restless soul. As he tells us in the opening paragraph,

“...health, youth, and idleness often rendered my temperament importunate. I was restless, heedless, a dreamer; I wept, I sighed, I desired a happiness about which I had no idea, and the deprivation of which I felt nevertheless.” (pp. 74)

This is the period in which he recounts exposing himself to young women in darkened alleyways, of longing for the intoxication of desire, and concurrently, a rise in “shame, the companion of the consciousness of evil”. Rousseau is scarcely over the calumny of Marion and the ribbon, still carrying the stain of his own indictment in his conscience. He embarks on his heiro-fountain scam, and appears unmoored from the foundations of home and social life.

So one might ask, is this not that quintessential time of juvenile crisis, in which a young man must subsequently find his great passion? At the least, Rousseau appears to be convincing us that he needs a vessel for self-expression - a way to focus his life’s energies. He has framed his prior life experiences to prime the reader for the imminent entry of an external salvation, a defining thing which might give his life greater meaning. If that thing were to be a some-one, then our best guess would be that it would be Madame Françoise-Louise de Warens. But the fullness of our reading betrays her. We know that, eventually, She does not define Rousseau’s public life, nor does she share in his victories. Music, however, is the some-thing that does. Music is with Rousseau, more or less, from the time his public rise commences, to the point his fame crests in book eight and (in his presentation) his personal calamities begin to advance.

And so the stage is set for music’s entry into Rousseau’s life. He presents it to us innocuously at first, referencing the book of music which Mme de Warens provides him as he enters the Seminary to commence his studies. He has a perplexing attitude toward the woman who first opens his ears to music, showing simultaneous gratitude and contempt for her early attempts to educate him;

“She had a voice, sang passably, and played the Harpsichord a little. She had had the kindness to give me some singing lessons, and it was necessary to begin from the beginning, for I hardly knew the music of our Psalms. Far from putting me in a condition to sol-fa, eight or ten very much interrupted lessons from a woman did not teach me a quarter of the signs of music.” (pp. 98)

From a woman! The young, brash Rousseau is undoubtedly a little misogynistic. Penetrating further though, the implication of Rousseau’s dismissiveness of Mme de Warens could also imply an early determination of music as a high art necessarily defined by masculine intelligence: As would befit his time, music for Rousseau is an art that should be mastered by great men and taught in high places.

The birth of Rousseau’s musical reason

There are three constitutive elements to Rousseau’s musical reason. The first is intellectual compatibility. The second is emotional fulfillment. The third is public reward, which includes reputation, and social benefit.

In considering the intellect, it is important to note that prior to the commencement of his musical education in book three of The Confessions, Rousseau has presented the functioning of his own intelligence as analogous to a changing opera scene. He is recounting the problems he has as a young man in reconciling his intelligence and social temperament;

“Have you ever seen the Opera in Italy?...there reigns an unpleasant disorder… Nevertheless little by little everything is arranged, nothing is lacking, and one is completely surprised to see a ravishing spectacle following this long tumult” (pp. 95)

Opera, by conventional wisdom, is the highest of all the musical forms. It would make sense that a young man like Rousseau would draw an equivalence between his own functioning, and that of European high-art’s most treasured form of performance. Rousseau, at an early age, no doubt feels a compulsion toward musical activity. It reconciles with the complexity and scale of his intelligence’s architecture. It provides an adequate canvas for his romantic imagination, and crucially, it designates a counterpoint of reason for the prior struggles he has endured in the social presentation of his intellectualism. Music is a demonstration of artistic capacity in which the author may communicate the brilliance of his intellect publicly, without the accompanying test of social competency. A composer can sit motionless, silent, in an opera box, as his work’s glory reflects effortlessly on to him. Rousseau recognises his opportunity;

“My marked taste for this art gave rise to the thought of making me into a musician” (pp. 102)

Next, we must consider Rousseau’s emotional connection, not to music itself, but to the first environments of his music-making. His introduction to music comes from Mme de Warens, and in this first instance it is not hard to see the literal connection to the warmth he finds in her bosom. Mamma gave Rousseau his music, and he seeks emotional reward in incubating and returning it to her with improvements;

“In triumph I brought back her book of music of which I had made such good use….Music was performed at her house at least once a week” (pp. 102)

It is through Mme de Warens and these household performances that Rousseau also meets his other early guiding musical influence, M. Le Maitre. It is important to understand that although nominally his first real music ‘teacher’, it is the environment that Maitre fosters that fires Rousseau’s fond desire for a musical life. Certainly, he is clear in his judgment that Maitre is no maestro, but a kind man who’s tutelage exposes Rousseau to the sort of world he might hope to master;

“...a good composer, extremely lively, extremely gay, still young, rather well built, with little intelligence, but on the whole a very good man…One will judge very readily that the life of the master’s residence–always singing and gay, with musicians and children of the choir–pleased me more than that of the seminary with the Lazarist fathers…the remembrances of these times of happiness and innocence often come back to enrapture and sadden me” (pp.102-103)

Along with Le Maitre, Rousseau’s introduces another important male influence in book three of The Confessions. This man’s effect on the formation of Rousseau’s musical reason is decidedly less wholesome. M. Venture appears at the door of M. Le Maitre’s Annecy house mid-winter, in February 1730. Rousseau is immediately suspicious;

“Everything about him indicated a debauched young man who had some education and who did not go begging as a beggar, but as a fool” (pp. 104)

Despite this, Rousseau can not help but quickly form an attachment to Venture. He sees in him the allure of celebrity, the opportunity to win favour, and to advance the pursuit of sex and good favour;

“We talked about music, and he spoke about it well. He knew all the great virtuosi, all the famous works, all the actors, all the actresses, all the pretty women, all the Great Lords”

Through Venture’s example then, Rousseau has a pathway to the good life he seeks. Moreover, he shares with Venture the passion that might propel him there. Troublingly though, Venture’s musical reputation seems to be built on shaky ground. In book four, as the relationship develops and Rousseau cements his loyalty to Venture, it becomes apparent that Venture is at best a dilettante and at worst a musical fraud. All along, he has been incapable of serious musical discussion, and it now appears that he deigns to steal compositions from others, by which he might profit. He has been proven to be a good singer, on which a bulk of his fame has been built, however, a pretty voice does not make a ‘good’ musician, and Rousseau appears to fall victim to his scam;

“In the morning I showed my stanza to Venture, who, finding it pretty, put it into his pocket without telling me whether he had composed his own” (pp.117)

Venture then, is the generative source of the dishonest intellectual permissiveness which brings Rousseau unstuck later in book four. He says as much - explicitly - when faced with the dilemma of how to make ends meet in Lausanne. Invoking the example of Venture, he purports to teach music, but admits he is not suitably skilled to do so;

“Upon drawing near Lausanne I re-examined the poverty in which I found myself [and] the means to remove myself from it…I took it into my head to play the little Venture at Laussane, to teach music which I did not know, and to say I was from Paris where I had never been” (pp. 123)

It should be observed that it is not just the skills deficit of Venture that Rousseau imitates, but also the false-pretension of cultivation that lies implicit in the claim to a Parisian pedigree. In this way, Rousseau appears as a man made in the mold of Venture, not just a roustabout fudging his trade. It is further important to acknowledge that Rousseau, at least retrospectively in the writing of The Confessions, acknowledges the self-delusion under which he lives, in his taking after Venture;

“To understand to what point my head had turned at that time, to what point I was venturized, so to speak, it is necessary only to see how many extravagances I heaped up all at the same time”

Amongst these extravagances are the taking of a false name under which to write, the boasting of his talents as a composer, and the resultant commissioning by the law professor, Francois-Frederic de Treytorens, to write a piece (of suspiciously indeterminate formal parameters). As Rousseau does not record any detail about the work itself, we can reasonably assume that in his un-educated state, he produced a quite literal chunk of musical gobbledygook. That is what appears to have been the judgment of the musicians employed to perform it, who relate it as ‘unbearable’, ‘an infernal racket’ and ‘rabid music’. Rousseau is humiliated, and though the townsfolk are still kind to him, his incapacity is exposed, and his shame mounts.

I will return later in this essay to examine the significance of Rousseau’s sublime failure here. First, it is worth noting that after the peak of this delusional fancy, Rousseau has two further reflections on his musical employment, which both compound his shame, and encourage him to remedy his situation. The first of these is the admission that his decision to learn music by teaching it was ‘insensible’ (pp. 129). In this admission Rousseau begins to turn toward the recognition needed in order to reconcile and improve his situation. He is also able to admit the wrongdoing in regards to his friend Perrotet, who had sponsored and promoted his music teaching, and is still owed a significant sum of money. The second instance is the happy ‘accident’ of his being overheard by the monk, M. Rolichon, whilst singing in reverie outside of Lyon. Rousseau is again dishonest. He is still indebted, and lies about his musical expertise in order to secure employment as a copyist with the monk. Once more, his dishonesty is exposed when his scores are riddled with errors, and unusable to musicians. However, there is a clue that in this episode Rousseau sees not an opportunity for self-aggrandizement, but the chance at genuine self-improvement. As he negotiates with the monk, he concedes (at least to his readers) that he must use the commission to learn;

“He asks me if I have ever copied music? “Often,” I say to him, and that was true; my best way of learning was to copy it.”

He then expresses a sincere joy at the opportunity to redeem himself;

“I stayed there for three or four days, copying all the time when I was not eating; for never in my life have I been so famished or better nourished…I worked almost as wholeheartedly as I ate, and that is saying more than a little. It is true that I was not as correct as I was diligent.”

Despite the grandiosity of Rousseau’s Ventures in book four, the fact the book culminates with these two fleeting expositions of humility plants the seed for the thematic grouping of books five and seven. Rousseau reaches the outer limits of his own self-delusion, and must now turn inward to salvage what is left of his authentic love of music, in order to build it into a viable intellectual and artistic pursuit. Still, one cannot discount the driving forces of celebrity, arrogance, and hubristic decadence, as constitutive elements in the persona of Jean-Jacques Rousseau the musician.

It behooves the reader to realize too, that the wild adventurism of the musically immature Rousseau is not divorceable from the general milieu in which Rousseau moves at this stage of his life. Whilst we can trace the development of his music in isolation, and look poorly upon him for these episodes of dishonor, he does write a broad disclaimer at the end of book four, excusing himself in apologia;

“These long details about my earliest youth will have appeared very puerile and I am sorry about it: although born a man in certain respects, I was a child for a long time and I am still one in many others.” (pp. 146)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Autodidacte

At first, Rousseau’s interactions with the musical life in book five seem to mirror that of book three. There is his relationship to Mme de Warens, the home-tuition in singing, and the invocation of an idealized musical passion. But the book then takes a more determined tone. Rousseau carries the awareness of his past failings, and is focussed on their remedy, in tandem with the romantic coupling of music with his relationship with Mme de Warens;

“What is surprising is that an art for which I was born should nevertheless have cost me so much pain to learn, and with such slow success that after lifelong practice, I have never been able to sing surely by sight reading. Above all what made this study pleasant for me at that time was that I could do it with Mamma…by then I was almost as advanced as she was” (pp. 152)

So it appears that Rousseau has grown up. His next musical attachment is not to a charlatan, but rather, to Jean-Phillipe Rameau, arguably, the most important musician in 18th Century France. It is Rameau’s harmony that Rousseau is interested in, not singing, copying, or the other tangential aspects of musical literacy. This is important, because harmony is the true fundamental of the art of Western European tonal music. Rousseau knows that there are many paths to musical celebrity, but the serious and sustained study of harmony suggests true dedication to the art of composition. He devours Rameau, and then seeks to improve upon his principles, counter-studying the work of the Abbe Palais, with whom he aquaints himself;

“We were inseparable…He spoke to me of his principles; I compared them with those of my Rameau” (pp. 155)

Determined to gain real expertise, he steps up his performances for Mme De Warens, but this time not for love, celebrity, or favor, but rather for the utilitarian purpose of honing his skills of musical execution;

“I filled my head with accompaniment, concords, harmony. To do all this, I had to form my ear: I proposed to mamma a little Concert every month; she consented to it” (pp. 155)

Undergirding these activities is an important paradox, crucial to the understanding of how Rousseau learns, and his lifelong autodidacticism. Consider that in the brief periods of musical tuition, first with Mme de Warrens, then at the seminary, and later with M. le Maitre, Rousseau does not learn music effectively. That is evidenced clearly by his failures in book four. Yet in book five we encounter him in full time employment, more devoted than ever to his study, and learning music to great effect (as evidenced by his successes in books seven and eight). Rousseau presents a clear preference for self-directed learning, and seems to be both happier, and more receptive to knowledge, in this setting.

The irony, of course, is that this very success propels Rousseau to recommit himself to full-time pursuit of musical study. When he looks for a composition teacher to complete his training, he again recalls Venture, and seeks out his former composition teacher. Curiously, this effort to secure tuition runs awry in apparently unrelated circumstances.

This diversion, the failure to secure further tuition, serves to highlight the success that Rousseau enjoys as an auto-didact. For if his account is to be taken at face value, in lieu of having a mentor he persists with his study of Rameau by himself, teaches himself how to compose some short pieces, and is so successful that his patrons believe him to be plagiarizing, such is their disbelief that a man so poor a music reader could be so good a music writer;

“Since I read music so poorly, these Gentlemen could not believe that I could be in a condition to compose any that was passable, and they did not doubt that I had had myself given the honor for someone else’s work.” (pp. 176)

Though increasingly confident, he has trouble with score reading, and describes his frustrations in language which recalls the earlier metaphor of the slow moving opera scenery, and his general inability to ‘fire’ on the spot;

“At bottom I knew music extremely well, I lacked only that liveliness at the first glance that I have never had with anything, and which is acquired in music only by a consummate practice.” (pp. 177)

In this quote, with the reference to ‘at bottom’, we encounter a problem in assessing Rousseau and his music. I have stated earlier that, as regards Rousseau and music, books five and seven belong together as they are concerned with the development of musical skill. Although Rousseau is working hard and making fine progress in his objective musical capabilities, he nevertheless reminds the reader of the original, subjective nature of his project. Clearly, someone who is unable to fluently read a musical score could hardly claim to know music ‘extremely well.’ However, that is just the claim that Rousseau makes. Though he is increasingly concerned with communicating his growth of a technical, concrete knowledge of music, his self-judgment in communicating his inner feeling for music seems to win primacy in his scheme. This aligns with his general attitude to the presentation of the self throughout The Confessions. To Rousseau, it is not the objective measure of skill, morality, or competent execution of duties that provides the metric assessment of success or failure. It is rather, in the subjective, in the ‘knowing’ of self-truth, that Rousseau measures his worthiness. As he says in the very first paragraph of The Confessions;

“I have unveiled my interior as Thou hast seen it Thyself” (pp. 5)

Rousseau reminds us again of this mission in book seven, just prior to a further exploration of his concrete capabilities as a musician;

“The particular object of my confessions is to make my interior known exactly in all the situations of my life” (pp. 234).

Arriving then in Paris in 1941, he appears deeply enmeshed in the technical study of music. His knowledge of the concrete in music is advanced, and through 1942 he tries, unsuccessfully, to win the Academy over to his new system of musical notation;

“I did not succeed a single time in making myself understood and satisfying them…they refuted me with the aid of some sonorous phrases without having understood me…the Academy judged my System to be neither new nor useful” (pp. 239)

Rousseau’s writing here betrays an eagerness to communicate his technical skill, and to make a tangible contribution to the serious study of music. In book seven he is utterly unconcerned with presenting music through the lens of the romantic or the personal. His reflections belie his preoccupations;

“[Speaking of an intellectual rival] His ways of writing the seen notes of the Plain Chant without even dreaming about octaves in no way deserved to enter in parallel with my simple and convenient invention for easily noting with numbers any music imaginable, keys, silences, octaves, measures, tempos, and lengths of the notes…The biggest advantage of mine was to do away with transpositions and keys, so that the same piece was noted and transposed at will into whatever pitch one wanted by means of a presumed change of a single initial letter at the front of the tune.” (pp.239)

Book seven records several further achievements in Rousseau’s musical life. They include the publication of the Dissertation on Modern Music, the creation of his Ballet, The Gallant Muses, and his penning of articles on music for the Encyclopedia. He devotes extended passages to discussing musical form and style, including comparisons to the Italian school– an interest which blossoms through Rousseau’s proximity to the artistic life of Venice, in his role as secretary to the Ambassador.

Most importantly in this book, Rousseau discusses the composition of a full-scale Opera. This draws perfectly together the threads of philosophy, music, worldly ambition (and a little sex!), which run throughout his life and are reflected in The Confessions.

Read together, books five and seven are a detailed and comprehensive exposition of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s musical development. The writing on music in these books is geared toward technical detail and concrete accomplishment. Where romanticism, introspection and ‘the self’ do appear, they serve primarily to link Rousseau’s music to his broader aims within The Confessions.

Failing to succeed; Failing, to succeed

I have discussed earlier the nature of Rousseau’s project, and the linkage of his musical aims within the framework of The Confessions. Rousseau also claims that in addition to the prime goal of revealing the ‘interior,’ his book will also record the facts as they are - free of embellishment, good and bad;

“I have been silent about nothing bad, added nothing good…I have shown myself as I was, contemptible and low when I was so, good, generous, sublime when I was so”

Rousseau appears true to his word, at least when it comes to music. He uses the bad to undergird the success of the good, and no example is perhaps more powerful than the triumph of his Opera, The Village Soothsayer. To explore this, we need to return to book four. There we find Rousseau distressed. He is at the end of his youth, and his first shallow, juvenile attempt at finding musical stardom has failed;

“Poor Jean-Jacques; at that cruel moment you would hardly hope that one day in front of the King of France and all his court your sounds would excite murmurs of surprise and applause, and that in all the boxes around you the most lovable women would say to themselves in a low voice, “What charming sounds! What enchanting music! All these songs to go to the heart” (pp.125)

This is a peculiar moment in the text, as Rousseau is foreshadowing very deliberately the later success he will enjoy as a composer. As Christopher Kelly notes, Rousseau here is making explicit reference to the occasion of his Opera premiere in 1752. Rousseau does not often pull the reader forward though the narrative in this way, preferring to present his life’s journey without too strong an awareness of later events. Nonetheless, he sees fit to do so here, and so subsequently frames the failure of his first public composition as a necessary step along the path to musical redemption. That redemption is a critical moment in The Confessions, seeding Rousseau’s establishment as one of France’s foremost public intellectuals, and winning the favor of Louis XV;

“His Majesty does not stop singing with the most out-of-tune voice in his Kingdom: ‘j’ai perdu mon serviteur; j’ai perdu tout mon bonheur.’...they were to give a second performance of the Soothsayer, which verified the complete success of the first in the eyes of the whole public.”

The Soothsayer moment

The Soothsayer ‘moment’ is one of, if not the most seminal passages in The Confessions. There are a number of threads which meet in Rousseau’s recounting of the event which support this argument. Firstly, the chronology. This is the high point in the arc of Rousseau’s personal narrative. We are two thirds of the way through the work, Grimm has just appeared, the cast of conspirators is assembled, and by Rousseau’s own declaration, his fortune is about to turn for the worse;

“With this one begins the long chain of my misfortunes…Two Germans attached to the Prince were there. One called M. Klupffell…The other was a young man called M. Grimm. (pp.293)

Secondly, Rousseau’s great artistic passion, music, reaches full maturity, after a necessary period of toil. Thirdly, in the subject matter of the opera, Rousseau has executed an act of public philosophizing, deploying to the stage his philosophy of man in the state of nature. Finally, with a palpable relief, the vicissitudes of Rousseau’s preoccupations with sex and public notoriety are sated by the public reaction;

“I soon abandoned myself fully and without distraction to the pleasure of savouring my glory. Nevertheless, I am sure that at this moment the pleasure of sex entered into it much more than an author’s vanity…I have seen Pieces excite more lively outbursts of admiration, but never as full, as sweet, as touching an intoxication reign during a whole spectacle, and above all at the court on the day of the first performance. Those who saw this one ought to remember it; for the effect was unique” (pp.318)

In music, and through the singular triumph of The Village Soothsayer, Jean-Jacques Rousseau reaches the high point of his Confessions. It is important to examine the path Rousseau takes on his relationship with music, as it often provides a worthy avatar for the rest of his life’s journey. Certainly, music is central to The Confessions, and understanding its role in presenting Jean-Jacques Rousseau the musician, can only help the reader in forming a fuller picture of Rousseau the man.

Benjamin Crocker

December, 2021